Development until today

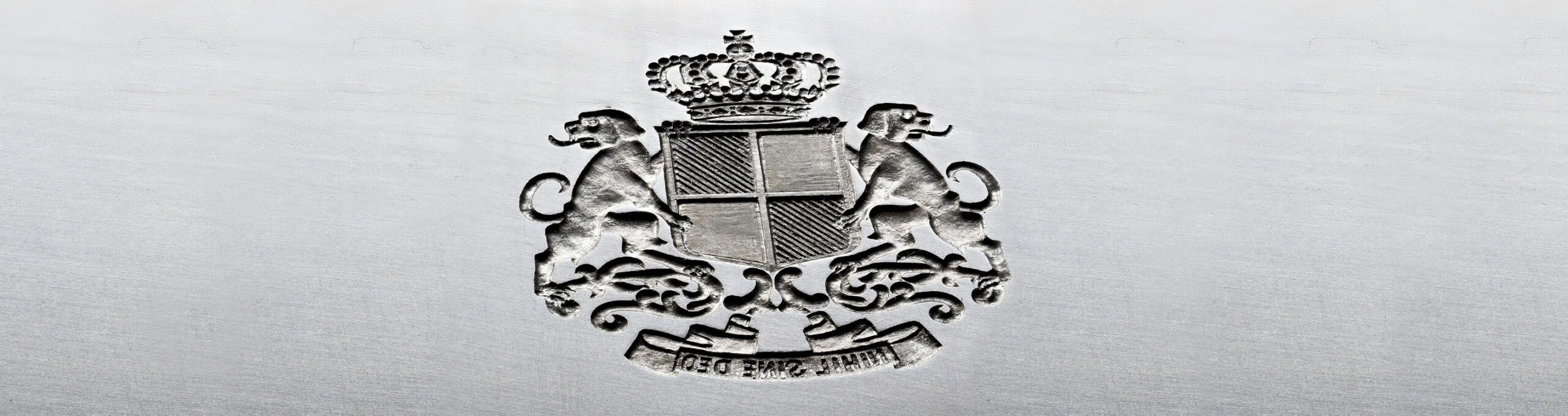

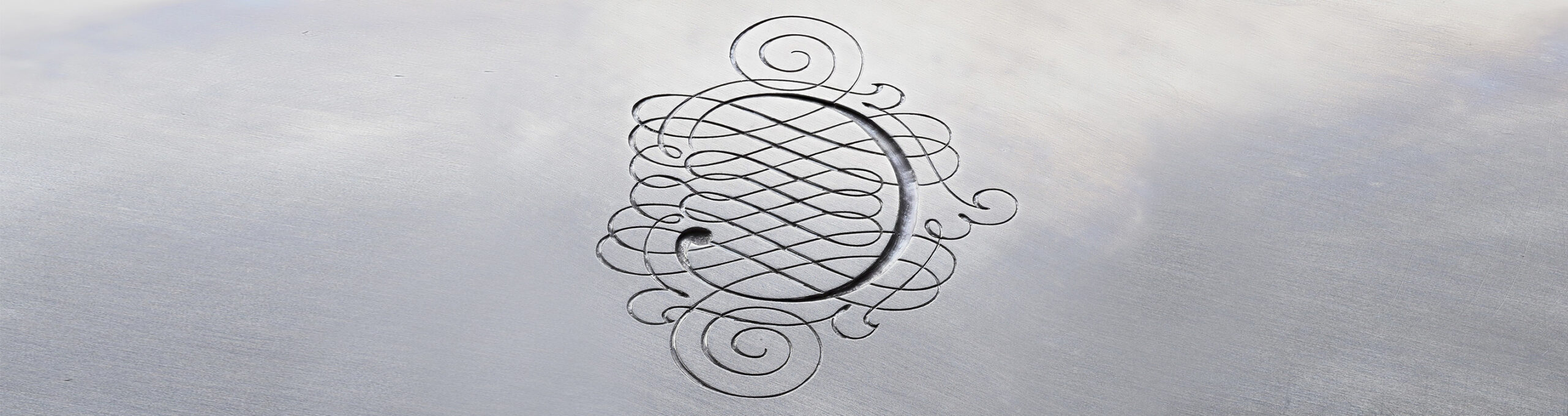

As with copperplate engraving, manual printing on the copperplate press was originally common for steel engraving. The printer first had to rub the color from pigment and binder himself. The plate was then colored with the pad and wiped clean again with cloths and paper. Only the deepened engraving now holds the color.

As desired, the printer could leave a touch of color on the plate surface and thereby also print a “plate tone”.

This technique is still used today by artists who do printmaking.

For the larger editions that the steel engraving was supposed to achieve, this technique of hand printing was far too laborious. With the onset of industrialization and the invention of the steam engine by James Watt, attempts were made to replace laborious manual labor with machine work. The first looms were built in England and a little later, around 1850, the English built the first steel engraving machine that was able to perform essential work steps mechanically.

The very heavily built machines had a simple inking unit that made it possible to recolor the plates with each print run. Wiping with cloths was replaced by a squeegee and a roll of paper that could wipe the engraving bright with every print run. The paper from the roll is pulled forward a little each time, so that new, unused paper is always available. This made it possible to produce embossings quickly and in large numbers.

The minting shops in England took advantage of the opportunity and were able to offer the many small and large manufacturers, including the industrial companies that sprang up everywhere, as well as law firms and private individuals, letterheads and business cards in a new, much higher quality than the customers were used to from the predominant letterpress printing process.

Like the loom, a few years later the new technology came to the continent, where it found many enthusiastic followers. Back then, the machines were built in such a way that the inking unit was on top and the engraving on the bottom. As it was common in printing at the time, the sheets were laid in and laid out by hand. Since the steel engraving / embossing process is a direct printing process, this inevitably meant that the printed image was on the underside of the sheet when the sheet was inserted. It took a lot of skill to take the sheet out of the machine without smearing the fresh embossing again. The sparse literature indicates that the skilled woman’s hands did this flawlessly. For decades, this was the only way to do machine-made steel engraving. In the new century, however, a tireless ingenuity came up with a remedy.

The “handling”, which is tedious for the embosser, has been made much easier by a completely new design. The designers simply turned the story around. Basically the idea was simple – they put the engraving upside down and the problem was – almost – solved. The new design came on the market under the name “inverted”.

Suddenly it was possible to see the result of the embossing immediately after the embossing process and also to take the sheet out of the machine again without risk. In addition, this also opened up the possibility of making two embossings on the same sheet by twisting the sheet. With the previously used construction, this screwing in would inevitably have destroyed the first embossing. Embossing was faster and paper could also be saved.

The last development step that the steel engraving presses underwent was the construction of the automatic feeder and delivery system around 1960. This enabled the paper to be automatically fed through the machine, as it was the case with the letterpress machines that were generally used at that time.

This automation also increased production. The hourly output has now been increased to approx. 1500 to 1800 sheets from the previously possible 500 to 880 stamps that a skilled embosser could do per hour. The machines have now become rare rarities, as the production of new steel engraving machines both by the manufacturer in England and by the licensee for a German replica of the machine was discontinued at the beginning of the 1970s.

Therefore, the machines in the factories are looked after very carefully.

Any maintenance and repair work must be carried out by the embosser himself. Even today’s machines still work with the technology of the founding fathers, only slight modifications have prevailed. All steel engraving machines are exclusively single-color machines and depending on the subject, sheet size, difficulty, color type, etc. it is decided which type is used.

Even today there is no steel engraving without the knowledge, skill, patience and passion of the person who made it.